When the folks at the New Yorker take a break from publishing stories about how spending thousands of dollars on watches is a legitimate form of therapy for Trump-election-induced depression, they feature some good stuff. Case in point, a short piece on "Hahaha vs. Hehehe", in which the author is baffled by, and trying to explore, the emergence of "hehe" as an alternative to "haha".

I will offer my personal interpretation of the different representations of laughter in text in a minute. But first: consider something so obvious that the author of the article does not even question: why do all representations of laughter (besides acronyms) include the letter 'h'? And not just in Germanic languages, but also in Greek, Chinese and, according to my mother-in-law, Arabic (where laughter is apparently represented as just "hhhhhhhh", without any vowels)? (Though different languages obviously use different letters to represent "h"; for example, the Spanish write "jajaja!" - which to me sounds like an overexcited German Shepherd responding to "do you want a cookie?")

The answer is obvious, but fascinating nevertheless: all humans use the same sounds when laughing, and the predominant sound in laughter is that of drawing a breath - which we all instinctively code as an "h". But although all languages (that I know of) have tried to standardise the orthography of laughter in a strikingly similar manner, laughter in real life varies by individual: a professor at Tulane claims that he could transcribe and then read back his friends' laughter with such accuracy that everyone could guess whose laughter he was reciting. That is not to say that individuals' laughter is invariable: it does change, to convey different levels of amusement or other emotions. Nevertheless, it seems that an individual's laughing patterns are quite unique. This observation in itself is moderately interesting, but hardly breakthrough: upon reflection, we'd all realise that we can recognise our friends by the sound they make when they laugh. But I find it amazing that linguists can actually transcribe laughter in such a way that it becomes recognisable.

Unfortunately, it is too much to expect every person to be able to accurately transcribe their laughter, which is why we resort to a common laughter-vocabulary consisting of the exclamations ha, haha (with "ha" potentially repeated a few more times; the reason I called out the single "ha" separately is that it can have a markedly different meaning, as I will discuss below), hehe, heh, hihi, hee hee, tee hee, ho ho, the prefixes mwah, bwah &c, the acronyms lol, rofl, lmao &c and various emoticons.

Of these, "ha ha" is the undisputed king, followed by heh and lol, according to Google Ngrams. All others are less popular:

Do note, however, that Google Ngrams tracks the appearances of a word in books, whereas emoticons and acronyms are far more popular online. Furthermore, the results above are not perfectly accurate, as some writers do not inject spaces between consecutive "ha"s or "he"s; I chose to ignore this in order to eliminate noise from "haha" or "hehe" being used in different contexts (I discovered that the Hehes are a tribe in Tanzania, for instance). Finally, some noise still remains - for example, "lol" also stands for "lots of love".

I therefore tried to validate these results by searching for these various words in my whatsapp chat history. Sadly, the search function doesn't give the number of hits, but eyeballing the data, I'd say that "haha" is indeed the most common, followed by "heh" - although the latter seems to be used almost exclusively by me. There are a few "lol"s, "hehe"s and various emoticons, but no "hee"s, "lmao"s or "rofl"s. Let's now look into these exclamations/acronyms/emoticons in more detail:

Ha

The author of the New Yorker article writes that "ha" is the basic unit of written laughter; that's true, inasmuch as the syllable "ha" is a constituent of "haha", but it's misleading: "ha" on its own is not actually used to express laughter or even amusement so much as surprise, suspicion, triumph &c (according to Oxford Dictionary). The word has its origins in Middle English apparently, though the dictionary doesn't give any sources.

That said, it's true that "ha" is also used for laughter. Well, sort of. I think most people use it as an acknowledgment that something intended to be amusing was said. The prankster who has so far tricked the CEO of Barclays and the Governor of the Bank of England uses it (in character) to applaud his own humour/cunning:

"If you ask for the crystal glasses you’ll be able to admire [the waitresses'] enchanting dexterity. I keep those glasses low down, ha! You don’t reach my age without knowing all the tricks." and

"What else would Mack the Knife do but support those he can trust in!

Begs the question, who should we seek to silence next!?

Onward, to bigger, and better things.

I may have already had a stiff one, it’s been a long day, and I get no younger.

Clapton has nothing on me ha!"

(To me, this usage seems so idiosyncratic that I am surprised that it by itself didn't give away the fact that the emails were a prank.)

Haha (& so on)

"Haha"'s preeminence is confirmed by Oxford Dictionary, which redirects queries for "hehe" to it. According to the dictionary, "haha" is first recorded in Old English, though again, there are no examples (apparently it appears in Hamlet, though it seems that it's actually meant to express surprise instead of laughter). Also, note that Garner says "ha-ha" is the correct spelling.

In accordance with both the Ngrams results and the OED, most of the people who responded to my question on facebook on what words they use to express laugther said that "haha" or "hahaha" is their preferred choice. In their words, "hahaha is more expressive, whereas the other ones are too descriptive", and "the number of consecutive 'ha's is proportional to the volume of laughter".

(One exception: one friend said he uses "hahaha" when laughing at people, and generally seems to attribute a mocking tone to "haha".)

Personally, I use "haha" when only mildly amused, and "hahaha" when I find something genuinely funny. A quick search of the term in my family's whatsapp group (aptly named "Bantercats") reveals that "hahaha" is the most common variant, followed by the standard "haha". There was also a "hahahahaha" from my brother in response to this picture of a hotel room in Tianjin:

(I was put up at that hotel after my flight was cancelled due to bad pollution (that's a thing that happens here) - I pulled the curtains to look outside and found out the room had no window. I don't think they understand the function of curtains in that hotel.)

Heh

Urban Dictionary defines "heh" as "half-laugh, semi-cynical connotation, used on IRC by those too cool to say lol or roflmao". (Here's the word's self-proclaimed inventor.)

I use "heh" to indicate a drier sort of amusement than "haha"; a more detached kind, perhaps, or even slightly patronising (for example, I used "heh" in response to being told that the Chinese call Plato "Bolatu").

At other times it serves as a neutral response. In these cases, it serves to let my interlocutor know that I've seen their message, and that I am well-mannered enough to respond, without actually putting any effort into my response.

Interestingly, the New Yorker writer says that "heh" may have some down-home vulgarity undertones. I had never interpreted it this way, but David Foster Wallace does use "heh" in Brief Interviews with Hideous Men to transcribe the conspiratorial and sleazy banter between two men, one of whom has taken advantage of a vulnerable woman's grief to sleep with her. So I suppose there is something in this view.

Finally, "heh" is used to represent sinister laughter in some comic books, e.g.:

Hehe

Again according the UD, "hehe" refers to muffled laughter, with a sneaky aspect to it. Indeed, everyone seems to attribute similar characteristics to it - my facebook friends assigned "tongue-in-cheek" or "snigger" tones to it, and this academic article says that "hehehe" is a "cynical variant of hahaha".

(Searching for "hehe" in my whatsapp messages yields 13 hits. Of these, 11 "hehe"s come from the same person. I wonder what that says about him.)

Unlike the New Yorker writer then, I do not see "hehe" as an alternative to "haha": they serve different purposes. One interesting question though: do the people who use this variant do it consciously every single time? Do they intend to communicate this "nudge-nudge", "wink-wink" attitude? What I mean is, do people think "okay, I want to show I am being cheeky, so I will specifically write 'hehe'", or do they subconsciously write "hehe" because they are feeling cheeky?

It'd be quite something if the latter - it would show that our intuitive understanding of the various undertones in laughter exclamations has been ingrained in us.

Hihi, hee hee, tee hee, ho ho

All of these are far less common variants. I agree with the New Yorker writer that the first three are cutesy, possibly too cute, as she puts it. To me, they look a bit artificial - they give the impression one specifically chose to use them instead of their flowing naturally, and so they can be a bit jarring. In fact, I don't think I've ever seen "tee hee" anywhere except this famous bash.org quote.

(Note that "hihi" is increasingly being used as a greeting instead of as a stand-in for laughter - and that's the definition given by the Urban Dictionary.

As for "ho ho", its most notable variant is Santa Claus's "ho ho ho". It, along with all previous variants, also appears in comic books when the artists want to show that different characters have different laughter:

Prefixes: bwah, mwah

The former of these is used to express explosive or hysterical laughter, but it's not very common in text speak.

The latter is interesting though: it is universally recognised as evil laughter. Up to this point, all variants have been abstractions, or the greatest common denominators, of individuals' laughter. Though simplified, they have been representations of the ways people actually laugh - earnest laughter, cheeky laughter, cool and detached laughter, mocking laughter - these are all real.

But evil laughter? This is the only one that is an invention. No-one is evil in their own narrative; no-one actually says "mwahaha, I will destroy earth and kill billions of people!". Granted, some people are deranged and may laugh while plotting atrocities - but the thing is, "mwah haha" does not have a mad quality to it. So out of all the exclamations we have discussed up to now, this one is the only one that is purely fictitious.

Acronyms

I am going to put this out there: I consider "lol" and its kin to be signs of intellect deficiency. Though I have at times used them myself, they seem to me a less refined version of "heh" (a view shared by the Urban Dictionary, as mentioned earlier).

I dislike them for several reasons. First, they have lost their meaning: "lol" is supposed to mean "laugh out loud", but no-one interprets it this way - as a frequent user of "lol" wrote on facebook, "[if I actually laugh out loud] I say 'literal laugh out loud'". And no-one literally rolls on the floor laughing, and I am not sure what "laughing my ass off" is even supposed to mean. So it seems to me that using "heh" is more sincere.

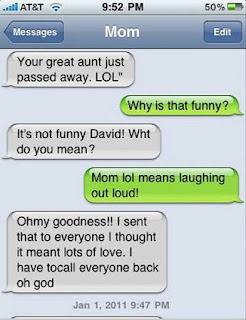

Second, "heh" is easier to read, process and interpret than "lmao", "rofl" and even "lol", with which older people are unfamiliar:

Third, "lol" especially is often used a neutral filler - for example, "I am not sure what to have for dinner lol". Fillers such as "like" are bad enough in speech; we shouldn't be introducing them into prose. They serve no function that cannot be served more elegantly, and more considerately for the reader, by other means.

For one thing, "lol" makes the writer come across like a prepubescent boy; for another, sentences like the one above (which are sadly quite common) are hard to parse: the reader expects the sentence to end at "dinner" but is then confronted by an unexpected word, without any punctuation. This is taxing and unnecessary. Writing badly due may be excusable; doing so on purpose is not.

Emoticons/Emojis

First of all, I must confess I did not know the difference between emoticons and emoji. Apparently, the former are textual representations of smiley faces (or other things) - e.g. :). Emojis are actual pictures - e.g.

Given the plethora of different emoticons/emoji, it is easy to find one that perfectly fits the writer's intended purpose, and so there is less ambiguity than there is in, say, using "haha" vs "hehe".

My personal take on this increasingly popular form of prose is that emoticons are, generally speaking, good and emojis bad. Emoticons are useful: they are a quirky way of efficient, speedy communication. If you have dinner plans with a friend, and they cancel because they caught a cold, you can send a sad face - :(. This expresses your sadness that they are ill and that you won't see them more efficiently, and perhaps more kindly, than a "oh man, bummer" - which may come across as having slightly accusing undertones.

They also slightly enrich language. When someone at work thanks you for something, or compliments you, you can respond with :D, instead of writing "no problem" (boring), "you're making me blush" (silly) or "oh I'm not that great" (falsely modest).

Emojis serve the exact same purposes, but they are, in their vast majority, unbearably ugly. Look at gtalk's latest crop of smiling faces:

Look at them! They look like melted blobs of cheddar. They are horrible. Facebook's aren't much better either. Furthermore, they are jarring when inserted in text. Emoticons are way less invasive and annoying. What really bugs me is that most apps now automatically translate emoticons into emoji. Meh.

Usage guide

Anyways, to recap, use:

I will offer my personal interpretation of the different representations of laughter in text in a minute. But first: consider something so obvious that the author of the article does not even question: why do all representations of laughter (besides acronyms) include the letter 'h'? And not just in Germanic languages, but also in Greek, Chinese and, according to my mother-in-law, Arabic (where laughter is apparently represented as just "hhhhhhhh", without any vowels)? (Though different languages obviously use different letters to represent "h"; for example, the Spanish write "jajaja!" - which to me sounds like an overexcited German Shepherd responding to "do you want a cookie?")

The answer is obvious, but fascinating nevertheless: all humans use the same sounds when laughing, and the predominant sound in laughter is that of drawing a breath - which we all instinctively code as an "h". But although all languages (that I know of) have tried to standardise the orthography of laughter in a strikingly similar manner, laughter in real life varies by individual: a professor at Tulane claims that he could transcribe and then read back his friends' laughter with such accuracy that everyone could guess whose laughter he was reciting. That is not to say that individuals' laughter is invariable: it does change, to convey different levels of amusement or other emotions. Nevertheless, it seems that an individual's laughing patterns are quite unique. This observation in itself is moderately interesting, but hardly breakthrough: upon reflection, we'd all realise that we can recognise our friends by the sound they make when they laugh. But I find it amazing that linguists can actually transcribe laughter in such a way that it becomes recognisable.

Unfortunately, it is too much to expect every person to be able to accurately transcribe their laughter, which is why we resort to a common laughter-vocabulary consisting of the exclamations ha, haha (with "ha" potentially repeated a few more times; the reason I called out the single "ha" separately is that it can have a markedly different meaning, as I will discuss below), hehe, heh, hihi, hee hee, tee hee, ho ho, the prefixes mwah, bwah &c, the acronyms lol, rofl, lmao &c and various emoticons.

Of these, "ha ha" is the undisputed king, followed by heh and lol, according to Google Ngrams. All others are less popular:

Do note, however, that Google Ngrams tracks the appearances of a word in books, whereas emoticons and acronyms are far more popular online. Furthermore, the results above are not perfectly accurate, as some writers do not inject spaces between consecutive "ha"s or "he"s; I chose to ignore this in order to eliminate noise from "haha" or "hehe" being used in different contexts (I discovered that the Hehes are a tribe in Tanzania, for instance). Finally, some noise still remains - for example, "lol" also stands for "lots of love".

I therefore tried to validate these results by searching for these various words in my whatsapp chat history. Sadly, the search function doesn't give the number of hits, but eyeballing the data, I'd say that "haha" is indeed the most common, followed by "heh" - although the latter seems to be used almost exclusively by me. There are a few "lol"s, "hehe"s and various emoticons, but no "hee"s, "lmao"s or "rofl"s. Let's now look into these exclamations/acronyms/emoticons in more detail:

Ha

The author of the New Yorker article writes that "ha" is the basic unit of written laughter; that's true, inasmuch as the syllable "ha" is a constituent of "haha", but it's misleading: "ha" on its own is not actually used to express laughter or even amusement so much as surprise, suspicion, triumph &c (according to Oxford Dictionary). The word has its origins in Middle English apparently, though the dictionary doesn't give any sources.

That said, it's true that "ha" is also used for laughter. Well, sort of. I think most people use it as an acknowledgment that something intended to be amusing was said. The prankster who has so far tricked the CEO of Barclays and the Governor of the Bank of England uses it (in character) to applaud his own humour/cunning:

"If you ask for the crystal glasses you’ll be able to admire [the waitresses'] enchanting dexterity. I keep those glasses low down, ha! You don’t reach my age without knowing all the tricks." and

"What else would Mack the Knife do but support those he can trust in!

Begs the question, who should we seek to silence next!?

Onward, to bigger, and better things.

I may have already had a stiff one, it’s been a long day, and I get no younger.

Clapton has nothing on me ha!"

(To me, this usage seems so idiosyncratic that I am surprised that it by itself didn't give away the fact that the emails were a prank.)

Haha (& so on)

"Haha"'s preeminence is confirmed by Oxford Dictionary, which redirects queries for "hehe" to it. According to the dictionary, "haha" is first recorded in Old English, though again, there are no examples (apparently it appears in Hamlet, though it seems that it's actually meant to express surprise instead of laughter). Also, note that Garner says "ha-ha" is the correct spelling.

In accordance with both the Ngrams results and the OED, most of the people who responded to my question on facebook on what words they use to express laugther said that "haha" or "hahaha" is their preferred choice. In their words, "hahaha is more expressive, whereas the other ones are too descriptive", and "the number of consecutive 'ha's is proportional to the volume of laughter".

(One exception: one friend said he uses "hahaha" when laughing at people, and generally seems to attribute a mocking tone to "haha".)

Personally, I use "haha" when only mildly amused, and "hahaha" when I find something genuinely funny. A quick search of the term in my family's whatsapp group (aptly named "Bantercats") reveals that "hahaha" is the most common variant, followed by the standard "haha". There was also a "hahahahaha" from my brother in response to this picture of a hotel room in Tianjin:

(I was put up at that hotel after my flight was cancelled due to bad pollution (that's a thing that happens here) - I pulled the curtains to look outside and found out the room had no window. I don't think they understand the function of curtains in that hotel.)

Heh

Urban Dictionary defines "heh" as "half-laugh, semi-cynical connotation, used on IRC by those too cool to say lol or roflmao". (Here's the word's self-proclaimed inventor.)

I use "heh" to indicate a drier sort of amusement than "haha"; a more detached kind, perhaps, or even slightly patronising (for example, I used "heh" in response to being told that the Chinese call Plato "Bolatu").

At other times it serves as a neutral response. In these cases, it serves to let my interlocutor know that I've seen their message, and that I am well-mannered enough to respond, without actually putting any effort into my response.

Interestingly, the New Yorker writer says that "heh" may have some down-home vulgarity undertones. I had never interpreted it this way, but David Foster Wallace does use "heh" in Brief Interviews with Hideous Men to transcribe the conspiratorial and sleazy banter between two men, one of whom has taken advantage of a vulnerable woman's grief to sleep with her. So I suppose there is something in this view.

Finally, "heh" is used to represent sinister laughter in some comic books, e.g.:

Hehe

Again according the UD, "hehe" refers to muffled laughter, with a sneaky aspect to it. Indeed, everyone seems to attribute similar characteristics to it - my facebook friends assigned "tongue-in-cheek" or "snigger" tones to it, and this academic article says that "hehehe" is a "cynical variant of hahaha".

(Searching for "hehe" in my whatsapp messages yields 13 hits. Of these, 11 "hehe"s come from the same person. I wonder what that says about him.)

Unlike the New Yorker writer then, I do not see "hehe" as an alternative to "haha": they serve different purposes. One interesting question though: do the people who use this variant do it consciously every single time? Do they intend to communicate this "nudge-nudge", "wink-wink" attitude? What I mean is, do people think "okay, I want to show I am being cheeky, so I will specifically write 'hehe'", or do they subconsciously write "hehe" because they are feeling cheeky?

It'd be quite something if the latter - it would show that our intuitive understanding of the various undertones in laughter exclamations has been ingrained in us.

Hihi, hee hee, tee hee, ho ho

All of these are far less common variants. I agree with the New Yorker writer that the first three are cutesy, possibly too cute, as she puts it. To me, they look a bit artificial - they give the impression one specifically chose to use them instead of their flowing naturally, and so they can be a bit jarring. In fact, I don't think I've ever seen "tee hee" anywhere except this famous bash.org quote.

(Note that "hihi" is increasingly being used as a greeting instead of as a stand-in for laughter - and that's the definition given by the Urban Dictionary.

As for "ho ho", its most notable variant is Santa Claus's "ho ho ho". It, along with all previous variants, also appears in comic books when the artists want to show that different characters have different laughter:

Prefixes: bwah, mwah

The former of these is used to express explosive or hysterical laughter, but it's not very common in text speak.

The latter is interesting though: it is universally recognised as evil laughter. Up to this point, all variants have been abstractions, or the greatest common denominators, of individuals' laughter. Though simplified, they have been representations of the ways people actually laugh - earnest laughter, cheeky laughter, cool and detached laughter, mocking laughter - these are all real.

But evil laughter? This is the only one that is an invention. No-one is evil in their own narrative; no-one actually says "mwahaha, I will destroy earth and kill billions of people!". Granted, some people are deranged and may laugh while plotting atrocities - but the thing is, "mwah haha" does not have a mad quality to it. So out of all the exclamations we have discussed up to now, this one is the only one that is purely fictitious.

Acronyms

I am going to put this out there: I consider "lol" and its kin to be signs of intellect deficiency. Though I have at times used them myself, they seem to me a less refined version of "heh" (a view shared by the Urban Dictionary, as mentioned earlier).

I dislike them for several reasons. First, they have lost their meaning: "lol" is supposed to mean "laugh out loud", but no-one interprets it this way - as a frequent user of "lol" wrote on facebook, "[if I actually laugh out loud] I say 'literal laugh out loud'". And no-one literally rolls on the floor laughing, and I am not sure what "laughing my ass off" is even supposed to mean. So it seems to me that using "heh" is more sincere.

Second, "heh" is easier to read, process and interpret than "lmao", "rofl" and even "lol", with which older people are unfamiliar:

Third, "lol" especially is often used a neutral filler - for example, "I am not sure what to have for dinner lol". Fillers such as "like" are bad enough in speech; we shouldn't be introducing them into prose. They serve no function that cannot be served more elegantly, and more considerately for the reader, by other means.

For one thing, "lol" makes the writer come across like a prepubescent boy; for another, sentences like the one above (which are sadly quite common) are hard to parse: the reader expects the sentence to end at "dinner" but is then confronted by an unexpected word, without any punctuation. This is taxing and unnecessary. Writing badly due may be excusable; doing so on purpose is not.

Emoticons/Emojis

First of all, I must confess I did not know the difference between emoticons and emoji. Apparently, the former are textual representations of smiley faces (or other things) - e.g. :). Emojis are actual pictures - e.g.

Given the plethora of different emoticons/emoji, it is easy to find one that perfectly fits the writer's intended purpose, and so there is less ambiguity than there is in, say, using "haha" vs "hehe".

My personal take on this increasingly popular form of prose is that emoticons are, generally speaking, good and emojis bad. Emoticons are useful: they are a quirky way of efficient, speedy communication. If you have dinner plans with a friend, and they cancel because they caught a cold, you can send a sad face - :(. This expresses your sadness that they are ill and that you won't see them more efficiently, and perhaps more kindly, than a "oh man, bummer" - which may come across as having slightly accusing undertones.

They also slightly enrich language. When someone at work thanks you for something, or compliments you, you can respond with :D, instead of writing "no problem" (boring), "you're making me blush" (silly) or "oh I'm not that great" (falsely modest).

Emojis serve the exact same purposes, but they are, in their vast majority, unbearably ugly. Look at gtalk's latest crop of smiling faces:

Look at them! They look like melted blobs of cheddar. They are horrible. Facebook's aren't much better either. Furthermore, they are jarring when inserted in text. Emoticons are way less invasive and annoying. What really bugs me is that most apps now automatically translate emoticons into emoji. Meh.

Usage guide

Anyways, to recap, use:

- "ha!" for surprise or for pranking British bank CEOs.

- "haha" for laughter, and add more "ha"s in proportion to the funniness of the thing you are responding to. If what you are responding to something unexpectedly hilarious, you can add a "bwah" at the beginning;

- "hehe" when you're being cheeky;

- "heh" when you want to acknowledge receipt of a slightly amusing message or if you're a comic book villain;

- "hihi"/"hee hee"/&c when you're intentionally being cute, but bear in mind that it may come across as artificial and overdone.

- "ho ho ho" if you're Santa Claus/writing a Santa Claus story (and are not feeling adventurous enough to change his laughter);

- "mwah ha ha" if you're drawing a comic book villain. But bear in mind this'd imply a simplistic view of good and evil.

- A combination of the above if you're a comic book artist drawing several characters laughing at the same time;

- emoticons to enrich your prose - but do not overuse. It's good to be able to express yourself in a variety of ways; over-relying on emoticons may cause a decline in your ability to do so.

Do not use:

- "lol" and other acronyms;

- Emojis.

I hope this helps!